“Of the organs frequently affected among the returning soldiers were the teeth. Patients suffering from carious aching teeth were numerous. In most instances they presented evidence of serious malnutrition following disease and exposure, suppurative alveolitis was less frequent. Infection of many oral cavities showed that teeth had been sadly neglected ruing the campaign. In Cuba and Porto Rico [sic] I saw occasionally a soldier with a tooth-brush under the hat band, but I have reason to believe that most of the tooth brushes were either left at home or thrown away on the march, as unnecessary articles of the limited toilet outfit…Tooth extraction was a conspicuous and grateful part of the surgery at camp Wikoff. Hardly a day passed without two or three such operations.”

– Senn, Nicholas, Medico-Surgical Aspects of the Spanish American War, 1900, p. 200-201.

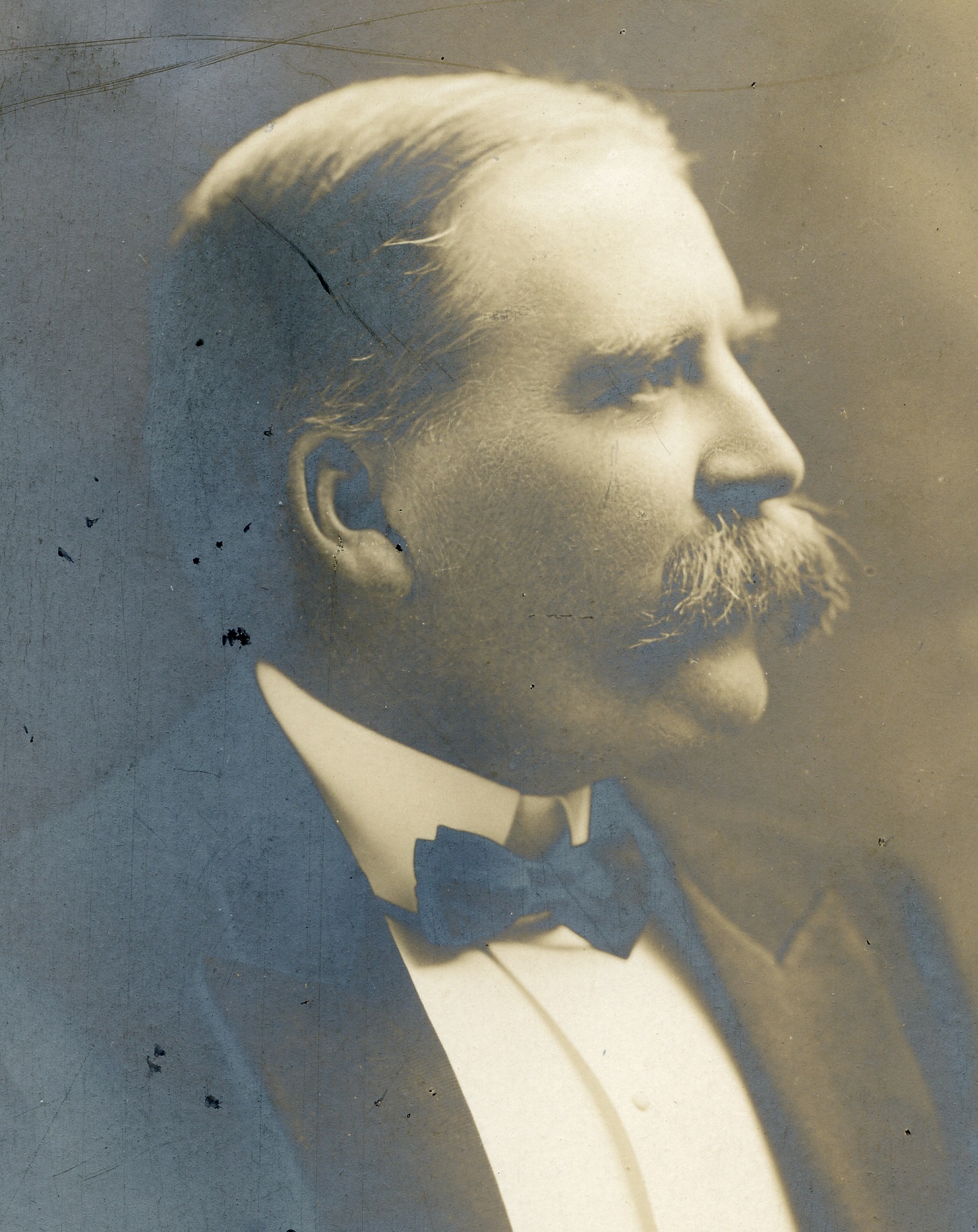

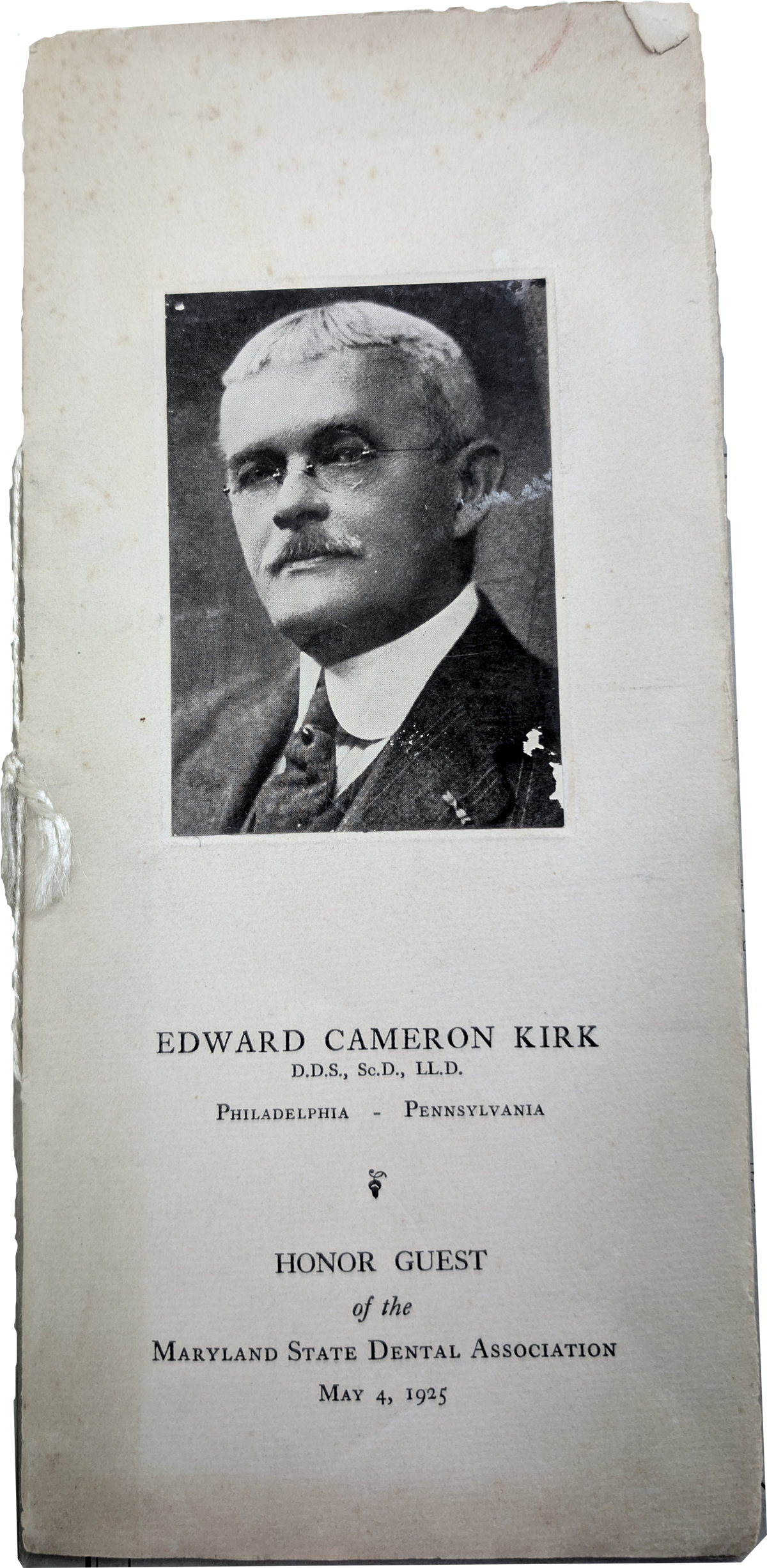

The Spanish American War (1898) and Philippine American War (1899-1902) would cement the need to organize a dental corps in the military, as the military was now on foreign soil, and trained dentists were in short supply. By 1899, B Holly Smith, Henry JB McKellops, and Williams Donnally from the Southern Dental Association reignited the discussion of establishing a dental corps, with a number of dental journal editors, like Edward Kirk of the Dental Cosmos, utilizing their platforms to advocate for dentists in the army and navy.

These civilian efforts in addition to dentists like William Ware and John Alvin Gibbon setting up the first overseas dental infirmary in the Philippines would directly lead to Congressman Peter Otey’s bill (HR 972) in 1899 that would become the basis for the amendment attached to the 1901 Army Reorganization Act (S. 4300) passed by congress to increase the efficiency of military establishment, which included the authorization of the Surgeon General to employ civilian contract dental surgeons in the Medical Department.

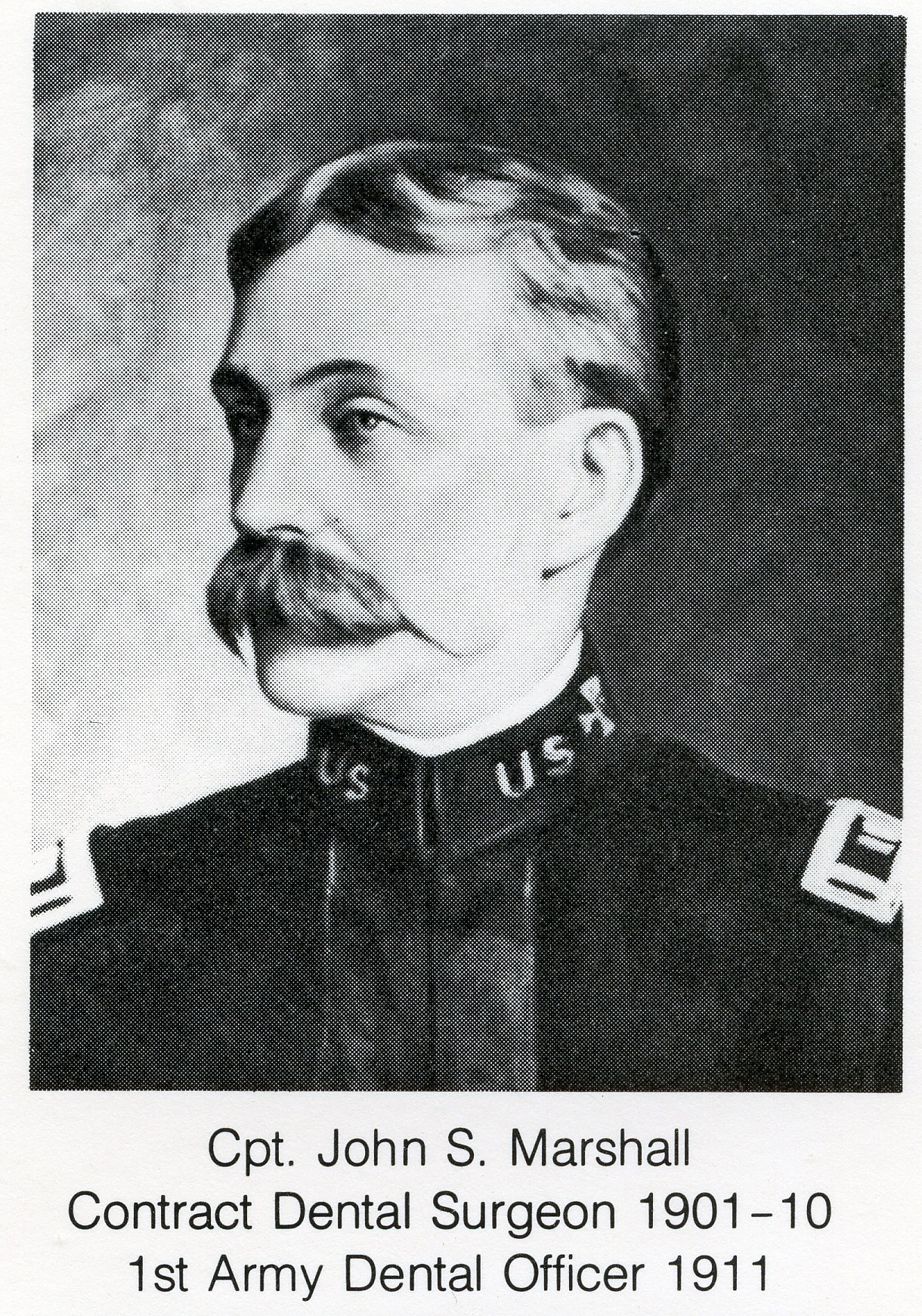

The Act allowed for the appointment of up to 30 civil contract dental surgeons, not commissioned members of the military, who would be approved by an examining board, initially composed of John Sayre Marshall (President of the Board and senior examining and supervising contract dental surgeon), Robert Todd Oliver, and Robert Morgan.

Excerpt from A History of dentistry in the US Army to World War II by Hyson, J., Whitehorn, W., and Greenwood, J.

Fitting Out the New Dental Surgeons

Contract dental surgeons were equipped with a special dental “outfit” especially prepared to meet the requirements of Army practice. Although designed for lightness and portability, it was considered better than what many starting dentists could afford. The portable dental outfit weighed about 450 pounds when cased and was designed to be carried by two horses or mules. It included an Army field desk, two folding chairs, and two folding tables. Canvas covers were provided to protect the cases from rain and moisture. Among the professional items in the outfit were a portable dental chair and a dental engine, packed in separate cases; burs, mandrels, stones, disks, and the like; excavators, chisels, scales, plastic-pluggers, gold-pluggers, rubber dam clamps, clamp forceps, a dam punch, extracting forceps, elevators, a steam sterilizer, and a hand cuspidor. In fact, the kit included all the instruments and adjuncts necessary to perform any operation upon the teeth except crowns, bridges, and artificial dentures. Each outfit contained supplies sufficient for 3 months’ service. The general hospitals and other posts designated by the surgeon general were furnished with an additional outfit, which included “a regular office operating chair, Allan bracket, cuspidor, instrument case, extra extracting forceps, and a full laboratory outfit for constructing vulcanite plates, swaged metal plates, interdental splints, crowns, and bridgework.”